The school run is the biggest safeguarding risk of all

The benefits of moving towards a people-centred community

In September 2020, Dolly Rincon-Aguilar caused a serious accident at her children's primary school in South London. A child was thrown into the air, others trapped under heavy machinery; four adults and five children were taken to hospital, some with life-changing injuries. One child needed emergency surgery to remove a blood clot. Others had serious leg, arm and eye socket fractures.

In any other circumstances - a trip or an assembly gone this wrong - what happened at Beatrix Potter Primary would have a significant impact on how schools operate. Health and safety guidance would be issued urgently for governing bodies and trustees to implement. Had Rincon-Aguilar acted deliberately, a serious case review would have reported by now. But she was just driving her children to school, accidentally pushed the accelerator instead of the brake, and crashed into a group of pupils and their parents. In July she was convicted of dangerous driving and fined £3,000, although she didn’t lose her licence.

Just driving the kids to school

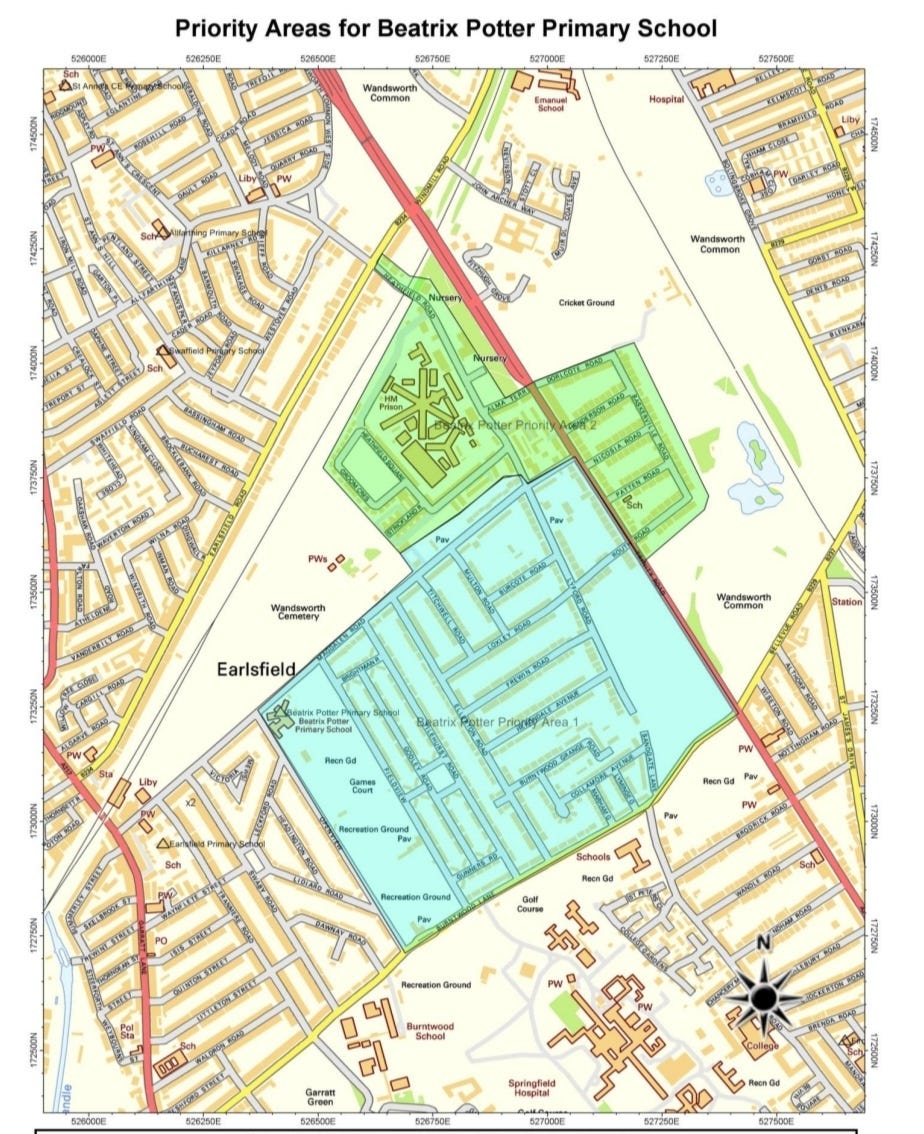

Obviously Rincon-Aguilar had no intention of causing such pain, and both the trial and media coverage made great play of how nice she is (as if that’s relevant to her driving competence), and her tearful apology to those she injured. But it’s difficult to overlook that she'd chosen to drive a 4x4 in Central London, an area embarrassingly well-served by public transport, to a school with a tiny catchment area (a local councillor confirmed no pupil lives more than 900m from the school) which had frequently asked parents not to drive their children there.

Anyone who’s seen the school run can only be surprised this doesn’t happen more frequently. At the primary school where I’m chair of governors, we need to have a traffic sub-committee. There's an enormous, free park and ride across the road, and a walking train from there, but some parents still choose to park in private driveways, drive along the pavement, and honk and hoot if others are in their way. My own road is exactly the same in the morning. And Oxford is supposed to be a “cycling city”, according to the signs on the way into town!

More widely, it’s obvious how much the school run contributes to traffic; anecdotally, it’s immediately noticeable how traffic drops away during school holidays. Sustrans say only half of primary-aged children walk to school, although a majority live within a mile of their school. Transport for London reckons a quarter of rush-hour traffic in London (where you'd expect fewer children to be driven to school, because of reliable public transport and shorter distances to schools) is the school run, equal to a single traffic jam 1000 miles long.

Private comfort, public catastrophe

More widely, the health and social impact of traffic on children is a safeguarding disaster. The government estimates that 36,000 people a year are directly killed by air pollution. In 2018 a coroner ruled that 9-year-old Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah had died because of asthma brought on by traffic in South London, near where Dolly Rincon-Aguilar and so many other parents drive their own children to school in comfy 4x4s. Ella was the first person in the UK to have air pollution recorded as a direct cause of death. Manchester University recently showed that traffic pollution in the UK has a direct impact on children's learning and memory, alongside the bigger impact of pollution on children's bodies.

The “war on motorists”

One of the greatest challenges in tackling this disaster is the extent to which society puts car use above everything else. Dutch journalists Thalia Verkade and Marco te Brömmelstroet set out how even the Netherlands had (and still has) a long and painful journey to a non-car-centred urban design. They point out how radio stations give more time to traffic news than actual news, and how everything is framed around allowing traffic or removing it. When Oxford council introduced parking permits and electric charging in my road, huge consultation packs were sent. Presumably a similar pack, on whether the same council should've slashed its social services and SEN support to the point of collapse, got lost in the post.

And like all other privileged majorities, car drivers lash out at any attempt to rebalance the status quo. Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, which are mainly an attempt to stop residential roads being used as sat-nav instructed rat-runs, lead to intimidation, vandalism and violence. No-one frames them as “quiet roads on which children should be allowed to play in safety”. Oxford has recently removed a few parking spaces from a beautiful square, which you’d think was a deliberate attempt to crash the city’s economy instead of creating a nice space for markets and sitting down. There are still 1000 parking spaces in the medieval city centre, reached on narrow residential roads, so the whole place jams up every weekend.

The only sustainable answer is removing the car completely from urban areas, accepting that its place is on motorways, and not risking its lethal violence against pedestrians and cyclists. This footage of a recent crash on the A40 in London - in a residential area with a speed limit of 40mph - shows the horrific force and violence we subject our communities to. King Charles gets it: “The pedestrian must be at the centre of the design process. Streets must be reclaimed from the car.”

What can be done?

Schools and their governing bodies have enough to deal with, but (in keeping with how we’ve accepted traffic violence) there’s no reason why we shouldn’t add traffic to the safeguarding concerns we try to mitigate. Why do we put so much emphasis on attendance and so little on the school run?

Ask your councillors and MPs for a School Street, which in London has had a greater impact (-18 per cent) on reducing car travel to school compared to the impact of coronavirus (-12 per cent). Don’t frame it around reducing traffic; frame it around making the school community as safe and pleasant for children and everyone else as possible.

This graphic shows how much more lethal a collusion at 30mph is, compared to 20mph. Are all the roads near your school 20mph, and enforced? If not, ask your local councillors why they’re risking pupils’ lives. The responsibility shouldn’t be deferred onto the most vulnerable - anyone not in a car - as the Highway Code has started to recognise.

And finally, what are your school's values and community relations? Unsurprisingly many children are extremely concerned about environmental damage and global warming; persuading their parents to drive them less is a clear, concrete first step for them to take.